(and surrounding areas)

THE WIYOT TRIBE AND OTHERS

A significant portion of this section is taken from the book An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian by Benjamin Madley. Consider most of what you read to be primarily direct quotes from this book unless otherwise noted with a “Source” The text here is not meant to represent original ideas or phrasing.

McKinley does not have a personal legacy in Humboldt County. But it was the same ideals that created a similar legacy in this, and surrounding, areas. These actions and this legacy are appalling. When asking why the McKinley’s statue should be relocated from its current location, it is important to again consider what McKinley perpetrated against many Indigenous Peoples of North America when he signed the Curtis Act (and how this mode of thinking profoundly harmed local Tribes). One must also consider the other nations seized by McKinley along with the mass killings and inter-generational cultural destruction this possession has required. It is a painful irony that one of Manifest Destiny’s champions has been placed centrally in a town that was, like many towns, the site of a bloody commerce in bodies and body parts. This should be an affront to any educated and compassionate person, as should efforts to minimize or explain away the complexities of this issue. “He fought to end slavery” is what some say. Did he not, ultimately, fight his hardest to enslave entire nations?

START AT THE BEGINNING

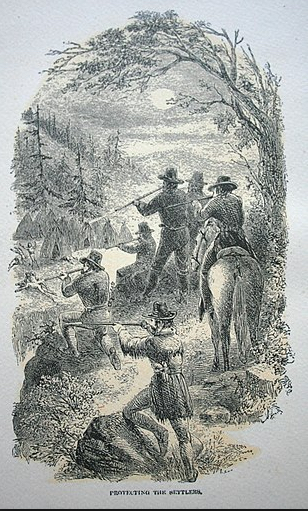

The Wiyot and other local Tribes have been here for millennia. The Wiyot’s ancestral territory occupies approximately 1000 square miles or about 1/3 of Humboldt County. It extends along the coast from Little River near Trinidad to the Bear River Ridge near Scotia and inland as far as Berry Summit and Chalk Mountain. Source.

From the Wiyot Tribe’s web page (most of this is direct quote)-

The first recorded “discovery” of Humboldt Bay by Europeans was in 1806 by Captain Jonathan Winship. Sustained contact began in 1849 when Josiah Gregg journeyed overland to Humboldt Bay. His party of explorers was met by Wiyot headman Ki-we-lat-tah on the day following their arrival at Humboldt Bay. According to L. K. Wood, Ki-we-lat-tah and his family rowed across the bay to greet the party of explorers, welcoming them with a feast of clams and providing them with “every means of comfort in his power.”

About 1500-2000 Wiyot people lived in their ancestral territory. The island is the site of the Wiyot People’s annual world renewal ceremony. The ground beneath Tuluwat village is an enormous clamshell mound (or midden). This mound, measuring over six acres in size and estimated to be over 1,000 years old, is an irreplaceable physical history of the Wiyot way of life. Contained within it are remains of meals, tools, and ceremonies, as well as many burial sites. The island is the site of the Wiyot’s traditional World Renewal Ceremony held annually to welcome the new year. This mound and other areas in and around Humboldt County would soon fall prey to desecration as grave robbers combed the sites for “artifacts”. The North Coast Journal published an informative article about this practice.

Before the

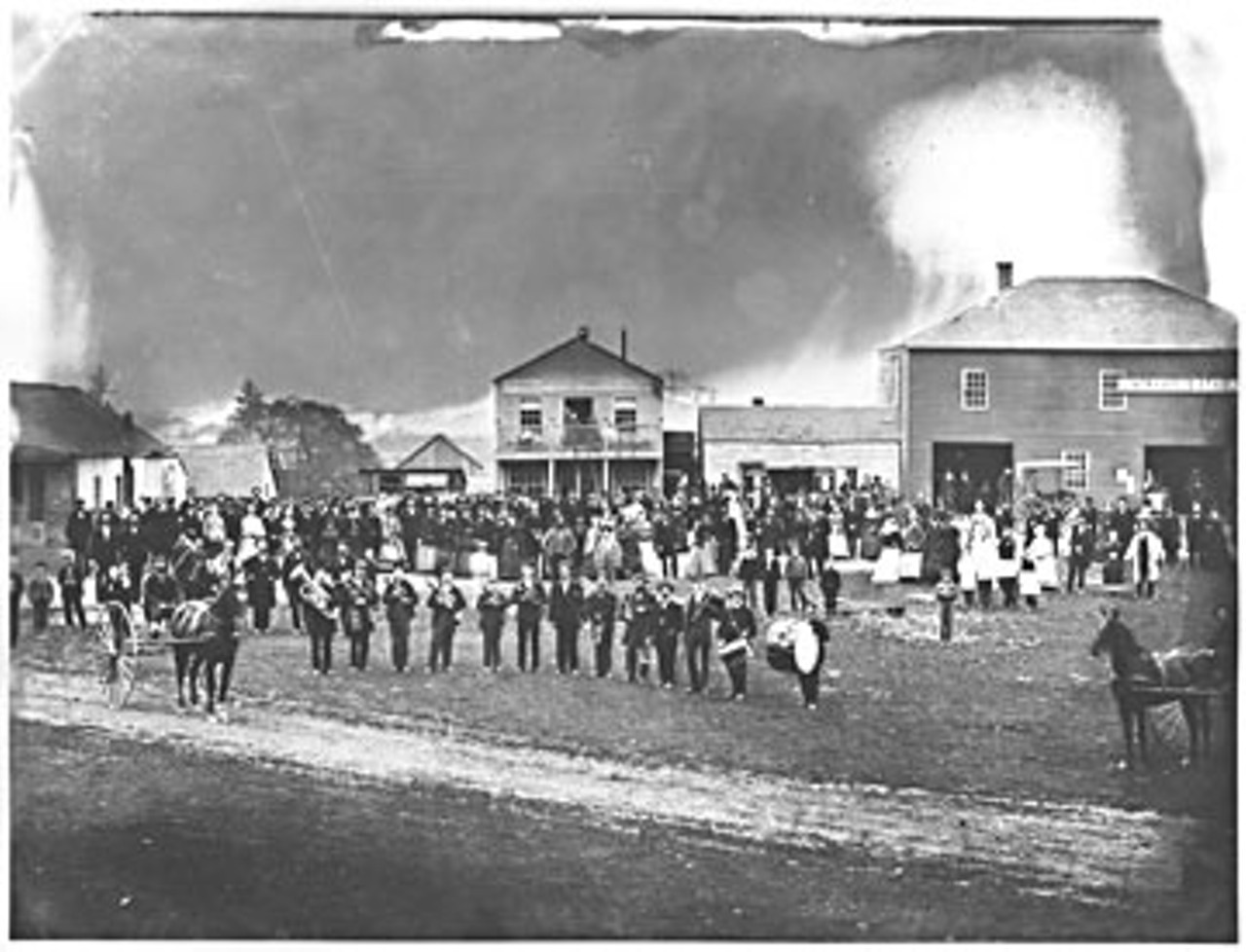

In late 1850, members of the Sonoma Gang, notorious for murdering Indigenous Peoples, began to take possession of land throughout what is now Arcata. Ben Kelsey took land just north of Foster Road. His brother Sam took land just southwest of where Arcata High School now stands. “Captain” Joseph Smith, who had led a local massacre on the peninsula, claimed the area around Sunset School. Ephraim Prigmore had located north of Samoa Boulevard, William S. Sansbury, who killed the first two Indigenous People’s on the bay, held what became the Plaza and lands southeast of it. Julius Graham occupied the area around the Arcata sports complex, while his brother Arthur owned much of what became Sunny Brae. Most of the fledging town belonged to the Sonoma Gang who had killed many Indigenous Peoples in Sonoma. Source.

Above: The Sonoma Gang on the Northwest side of the Arcata Plaza on April 26, 1870. North Coast Journal Source

Regarding these men, L. K. Wood would later write of the gang’s recent history: “four of the recruits were arrested for murder (Indian killing)….(Six should have been arrested, and five of the six hanged, as they never quit Indian killing, but kept it up after reaching here, which was the first cause of our Indian troubles.)” Source.

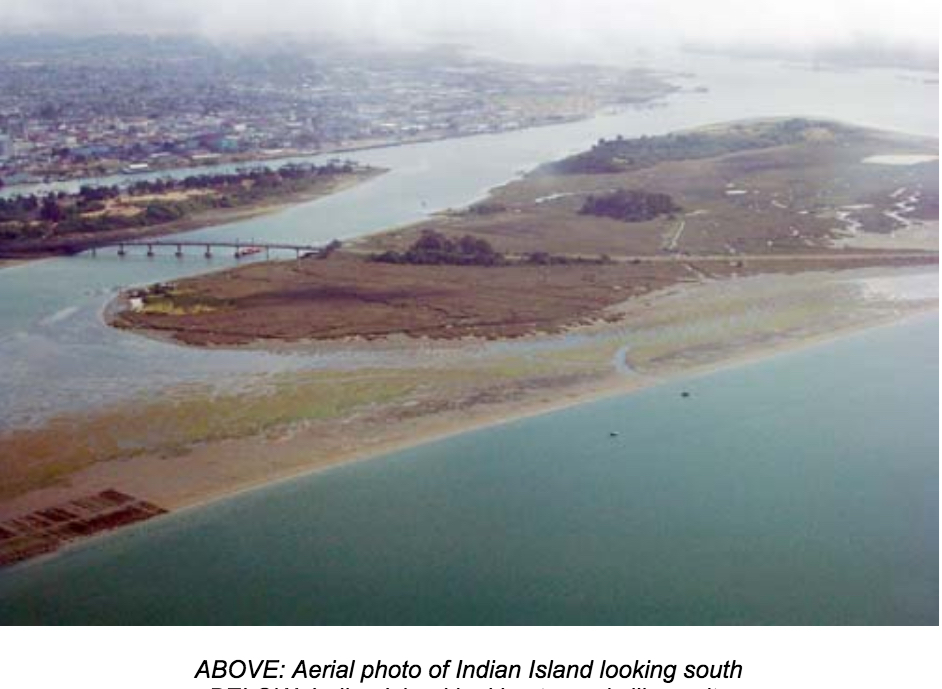

By 1851, map makers would include drawings of Humboldt Bay which lies in the heart of Wiyot land. Festooned with new settler names for places that already had Indigenous names, the increased detail in these maps reflected the increasing level of attention given to the area as the 1848 Gold Rush, and its infrastructure of towns, camps, roads, ranching, timber industry and, eventually, railways, progressed. Before further development and relative independence, the mining sections in the Trinity and Klamath mountains would obtain their supplies from the seaports and agricultural areas along the coast. The influx of settlers and the practices of genocide, ecocide and enslavement in the name of Manifest Destiny (and capitalism) would seriously threaten traditional ways of life, not just for the Wiyot. Source

An increasing number of white settlers began to occupy, dismantle and extract in areas already occupied by the the Wiyot and other Tribes. When it became clear that displacement was the norm and murder was the consequence for resistance (or attempts to adapt to settler-induced food shortages which was causing starvation), local Tribes became more active in defending their survival. If white settlers avoided acting in murderous ways that justified self-defense by the Indigenous Populations, they could expect to be left alone. One “Klamath river country informant” reported that with the exception of those instance where whites provoked at attack “there has been no hostile disposition manifested by the Indians towards the whites in general…(despite) years of making weekly trips through the heart of the country in which hostilities are reported…seen no disposition manifested to molest whites who behave themselves as white men should.”

The practice of legalized slavery of Indigenous Peoples expanded….

“Humboldt County became an infamous base for those ‘in the nefarious trade of stealing Indians.'” Source.

Human traffickers literally hunted and murdered Indigenous parents in the mountains in order to steal their children. The incentive was high when buyers would willingly pay $50 or $60 for a young child to cook and wait upon them, up to $80 for a ‘hog-driving boy’ or $100 (an amount equal to more than $2,700 today) for a “likely young girl,” according to a Dec. 6, 1861 story in the Marysville Appeal. Some of these children were kept by local families, but many were sold as far off as Colusa County, more than 200 miles away.” Source.

There was a person, up in Humboldt County, who was found with a small child, a young Indian child. And they ask him, “What are you doing with this child?” He said, “I am protecting him. He’s an orphan.” And they say, “Well, how do you know he’s an orphan?” He said “I killed his parents.” – Frank LaPena, Professor, Native American Studies Source

Indian Superintendent George Hanson in 1861 wrote “Indian survivors were either taken as prisoners or sold on the open market…while the troops are engaged in killing the men for alleged offenses, the kidnappers follow in close pursuit, seize the younger Indians and bear them off to the white settlements in every part of the country filling orders for those who have applied for them at rates, varying from $50 to $200 a piece.” Source.

Humboldt County also offered opportunity for young men lacking other prospects and families seeking a new life in the West. Pioneers could claim 160-acre plots of the area’s rich agricultural land, free, as long as they made improvements and established homesteads. Still other settlers were drawn to Humboldt to escape their pasts. The isolated coastal area, surrounded by towering redwoods on three sides and a formidable ocean to the west, was the perfect haven for “renegades … escaped convicts … and outlaws,” according to a March 23, 1861 military dispatch later published through an act of Congress. Source.

Above: The Little-Known History of Slavery in California: Lynette Mullen at TEDxEureka

Miners wanted to eliminate the risks posed by Indigenous Peoples so as to gain unfettered access to land and gold. Miners destroyed traditional means of subsistence and denied Indigenous Peoples access to what remained. When Indigenous Peoples would fight to survive starvation and repulse invasions and slave raiders this became a pretext for assaults by white settlers that were indiscriminate, disproportionate and intended to destroy entire groups regardless of their association with the alleged “crime” for which retribution was being dealt.

A miner describing the practice:

“About twenty or thirty miners, all armed with rifles, revolvers and bowie knives, would start out on a road into Indian country, discover a rancheria, take it by surprise, rush upon it and shoot, stab and kill every buck, squaw and papoose.”

In March of 1850, two Indigenous People from Eel River boarded a wrecked schooner, that had been mostly stripped by whites, to salvage ropes. Infuriated locals set out to find them and murdered the men, or perhaps just the first two Indigeneous men they found.

As the Trinity River attracted more miners, no tolerance was shown for Yurok people attempting to slow this destructive invasion and maintain their grip on a diminishing food supply. When several miners were robbed and wounded in April of 1850 “an expedition from Trinidad Bay destroyed five huts, killed several natives and captured one young woman.” Later that spring, prospector Thomas Gihon witnessed an attack on a Yurok Village north of Trinidad Bay in response to a theft. Later than day after several were killed “prospectors encountered a young Indian girl in the greatest distress, sobbing and waving her hands. We had doubtless killed her father or someone dear to her.”

At the junction of the Trinity and Klamath rivers in October of 1851, 24 local Tribes would sign a treaty with Colonel Redick McKee, one of the state’s Indian Agents, in an effort to make peace. The state legislature would soon reject this treaty and go so far as to develop a special commission that denounced the practice of Indian Agents attempting to set aside any land whatsoever for the Indigenous Peoples in Humboldt or anywhere else, and concluded that Indigenous Peoples should simply be removed from the state. California would go so far as to expand its campaign of genocide by accepting federal assistance to enhance its incentivization of murder. The US Senate approved “Benjamin’s Bill” in July of 1854. Within two years, the federal government had added $814,000 (or around 23 million in today’s currency) to California’s funding for a now state and federal partnership in a campaign of genocide against Indigenous Peoples. Enhancing the system of rewards, Congress promised 160 acres to any regular, militiaman, or volunteer who had participated in any such subsidized campaign for 14 or more days.

Above:

Above: An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873. Lecture by author and UCLA Associate Professor Ben Madley.

MILITARIZATION

From C. Oros (2016)

“In 1853 when the U.S. government recognized the clash between settlers and

Indigenous peoples occurring in the Humboldt Bay region, Fort Humboldt was

established in traditional Wiyot territory to militarize the region and protect settler

populations from conflict with Indigenous peoples of the area. The fort was also

established to maintain security on the bay as an important shipping port for timber and gold. Once again, little regard was paid to the natural environment or Indigenous peoples in the region. In fact, militarization brought incredible violence to Indigenous peoples. U.S. State policies and practices, as well as those of many settlers themselves, targeted Indigenous women in particular. The brutal violence that ensued – both genocidal and ecocidal in nature, what some also refer to as terracide, – continues to impact Indigenous peoples in the Humboldt Bay region to this day through what is often referred to as inter-generational trauma.”

TOLOWA:

How the name “Burnt Ranch” came to be

In 1853 about 450 Tolowa were massacred at Yontocket (Burnt Ranch):

“Pyuwa of Enchwo [a Tolowa Village], who lived to be a very old man, one of very few … survivors… People were gathered for Needash (World Renewal) after fall harvest, at the center of the world at Yontocket. Indians from all over gathered to celebrate creation and give thanks to the creator. On the third night of the ten-night dance, whites came into the village in the early morning hours. They torched the redwood plank houses, and as the Indians attempted to escape through the round holes in the houses, the militia killed them. This village existed as the largest native settlement consisting of over thirty houses. The whites would cut off the heads of the Indians and throw them into the fire. They lined their horses on the slough and as the Indians sought refuge, they were gunned down. One young Indian man ran out of the house with a “big elk hide” over his body, fought, and escaped to the slough. He stayed down there two or three hours: “All quiet down, and I could hear

The Tolowa were repeatedly targeted and subsequent massacres of their people would be carried out. The Tolow Dee-Ni Nation’s website is rich with information, including that of a massacre on January 1, 1855:

“On January 1, 1855, the Coast and Klamath Rangers along with the settlers of Smith River Valley descended on the Dee-ni’ gathered for Naa-yvlh-sri Nee-dash at ‘Ee-chuu-le’. The Dee-ni’ were trapped by water on three sides of the peninsula located between Lake Earl and Tolowa lagoons. Accordingly, the Crescent City Herald reported: “The die is cast and a war of extermination commenced against the Indians.” Dozens of victims were shot in the waters of the Lagoons as they attempted to swim away from the bloodbath. The results of this massacre left seven layers of bodies in the Dance House before it was torched.”

Source.

This timeline provides additional information on the genocide against the Tolowa.

THE KLAMATH & HUMBOLDT EXPEDITION

In December of 1854 a white man attempted to rape a Karuk woman and killed her male companion. In retaliation, the Karuks killed an ox they thought belonged to the man, which it did not. When they discovered their error, the Karuk offered the true owner compensation, which was refused. The Karuk understood what was to come, yet another pretext of mass killing. The subsequent indiscriminate and disproportionate killings of Indigenous Peoples by whites for the killing of an ox was a familiar pretext for such indiscriminate campaigns of murder. The participants in this and other campaigns would be financially compensated by the state and US government for their efforts. For the loss of one ox, all of the Karuk, Hupa and Yurok between the coast and the confluence of the Salmon and Klamath Rivers were targeted. Miners along the Klamath in Orleans spread that word that all local Karuks and Yuroks must immediately disarm or face death. On January 5th Stephen Smith from Big Bend wrote:

“We have organized ourselves up the river in order to exterminate the treacherous tribe that we now exist amongst.”

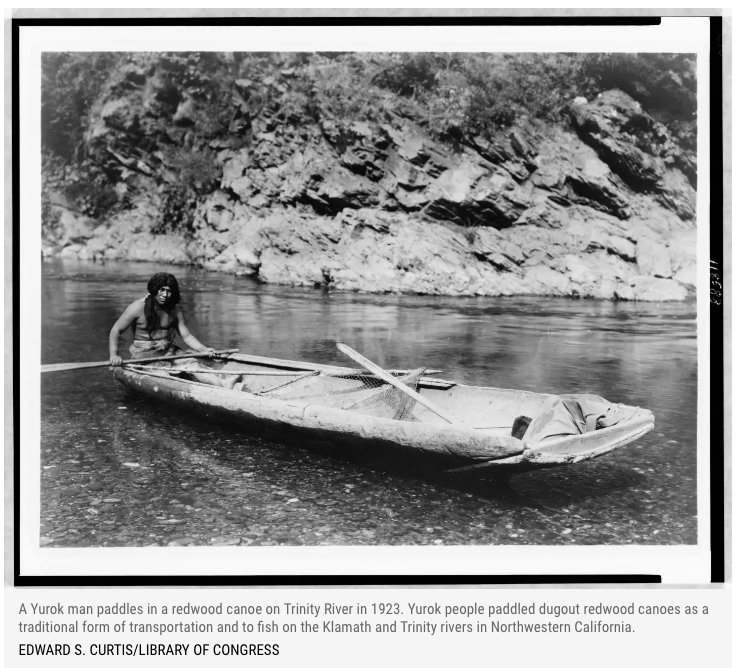

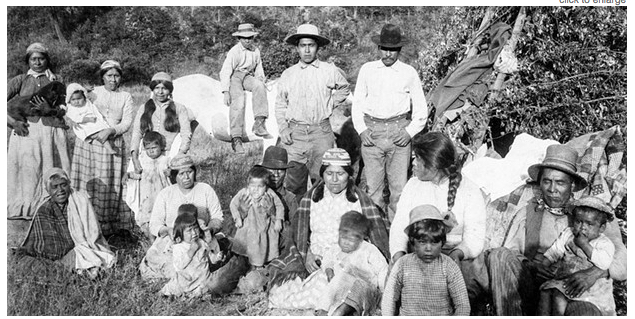

Above: Pictured here, images from different points in time are meant to depict the “ethnic cleansing of native population for settlers space for the sake of Westward expansion” that would have taken place in Humboldt County and the surrounding area. Source

The killings began on January 16th of 1855 when some of the Karuk and Yurok refused to disarm. This event became yet another catalyst for yet another justification for a broader campaign of state-funded murder. By January 23rd, 1855, 5 volunteer militia companies consisting of 253 men began their assaults. Coastal Yuroks were attacked and killed near Redwood Creek “and others at the lagoon.” Near a ranch, the militia would then kill 20 warriors and capture others. White men along the Klamath pursued “Indians to the mountains…are hunting them down like deer.” In March, a militia called the Klamath Rifles of Weitchpec “killed a large number of Indians”. On March 22, 1855, Militiamen “called the Indians from their homes

CHILULA

In September of 1856, Humboldt County white settlers murdered between 3 and 15 Chilula or Whikuts in their village when some cattle were found slain. Seven Wiyot were murdered when a white man reportedly received a mortal wound while in a village.

The San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin described the dynamic throughout California quite accurately:

“If Indians refuse to move upon the demand of settlers, a relentless course of punishments for the most trivial offenses is adopted, which is putting into operation without a declaration of war, the policy of extermination.”

All across California, the cycle of starvation, livestock killing and genocidal retribution was enacted on Indigenous Peoples. With the state and federal partnership adding further incentives to the expansion of murder-campaigns, the death toll was extreme.

One participant was rancher Drayden Lacock who testified in 1856:

“the first expedition by the whites against the Indians was made, and have continued ever since…there were so many of these expeditions that I cannot recollect the number…we would kill, on an average, fifty or sixty Indians on a trip…two or three times a week.”

It is estimated that he and his associates participated in the killing of thousands of Indigenous Peoples between 1856 and 1860. When one considers the number of people carrying out their own campaigns to extract a share of the state and federal rewards for doing so, genocide is an appropriate conclusion.

In February of 1857, the federal government added an additional $200,000 (about 5.5 million in today’s currency) for ten as-yet

In August of 1858, citizens of Humboldt and surrounding counties began to petition the governor for major militia operations against the Indigenous populations. Forty-eight US army soldiers would arrive at Fort Humboldt on September 19th.

During a public meeting in Arcata, some called for “a war of extermination, total extermination, of every man, woman and child whose veins coursed the blood of the Indian race.”

The Humboldt Times would echo this sentiment calling for forced removal and reservations, threatening that “a war of extermination will be waged against all who are caught off of it” and it would celebrate efforts to do so.

“We hope that Capt. Messic will succeed in totally breaking up or exterminating the skulking band of savages…”-Humboldt Times

On September 28th the governor ordered the enlistment of militiamen. Some 170 men volunteered, eager to take advantage of the opportunity to extract a living as murderers and further clear the areas rivers, creeks and valleys of people who might stand in the way of expansion.

Those living along the Mad River, Van Duzen and Eel Rivers were targeted as well as Redwood Creek. A woman and three children “died in a guardhouse”. Twenty Nongatl “in the Redwoods” were massacred and the remaining thirteen women and children captured. On January 21, 1859 at least thirty-five ment and fifteen women and children were taken prisoner after two detachments attacked thirty redwood houses. On January 28th, fifteen Wiyot warriors were slain and thirteen prisoners taken after an assault on of village of log houses.

By March of 1859

Video description: The towns of Marysville and Honey Lake paid bounties for scalps of Indigenous Peoples. Shasta City offered five dollars for every human head brought to city hall. And California’s state treasury reimbursed many of the local governments for their expenses. There were some 150,000 Indigenous Peoples in California before the Forty-niners came. By 1870, there would be fewer than 30,000. It was the worst slaughter of Indigenous peoples in United States history.

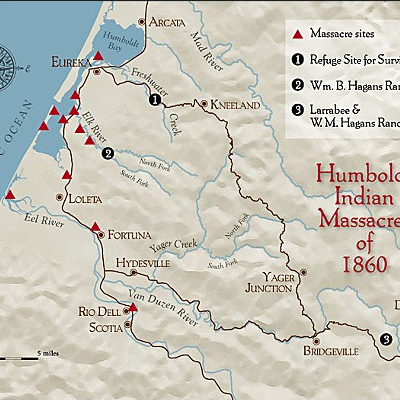

THE WIYOT MASSACRE

On May 24, 1859, white vigilantes organized at Hydesville to exact revenge for a reported killing of a white settler and the “theft” of cattle. A six-week long killing expedition followed. This would be repeated. In mid-December of 1859, white settlers in the Hydesville area raised a militia of a dozen vigilantes to protect stock and “hunt Indians” as the military at Fort Humboldt prepared to do the same. When two white men went missing near Mattole Valley, vigilantes massacred fifteen Mattole people and captured two others.

On February 6, 1860, with fishing season over, a vigilante group called the Humboldt Cavalry was organized by at least 46 Hydesville-area white settlers. In mid February, they attacked and killed 40 unidentified Indigenous Peoples at the Eel River’s south fork. Seeking to earn a living murdering Indigenous Peoples, and standing to each gain 160 acres for this “service”, they applied for enlistment as state militiamen. This was denied by the governor because this role was already occupied by the soldiers at Fort Humboldt. Additionally, as Major Gabriel Rains of Fort Humboldt would then point out, the state legislature was reviewing “the reports of a Committee adverse to payments to murderers of women and children…”

Following this rejection, enraged members of the Humboldt Cavalry “resolved to kill every peaceable Indian man, woman and child in this part of the country.”

Unaware of this declaration, Indigenous Peoples at Tuluwat on Duluwat Island across the bay from Eureka were gathered to celebrate their annual World Renewal ceremony. Members of the Wiyot, Eel and Mad River Tribes were present. At night, the men would replenish supplies, leaving the elders, women and children sleeping and resting. Early on the morning of February 26, 1860 a vigilante party crossed the bay around 4am and began murdering everyone there. The men brought no guns, hoping to club, stab and cleave their victims so as not to draw unwanted attention that would bring resistance back to the island. The victims were mostly women, children and the elderly.

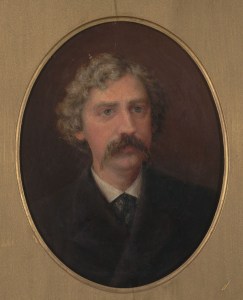

The multitude of their screams would cross the dark water that early winter morning and be heard by at least one Eureka resident, Robert Gunther who “owned” part of the island. He would later recall “it was said that about 250 Indians were killed that night.” 157 years later, wealthy resident and landowner Rob Arkley would lament the notion of returning this island to the Wiyot Tribe:

Bret Harte, a local journalist who was later driven out of town for his sympathetic views wrote:

“Neither age or sex had been spared. Little children and old women were mercilessly stabbed and their skulls crushed with axes. When the bodies were landed at (Arcata), a more shocking and revolting spectacle never was exhibited to the eyes of a Christian and civilized people. Old women, wrinkled and decrepit lay weltering in blood, their brains dashed out and dabbled with their long grey hair. Infants scare a span long, with their faces cloven with hatchets and their bodies ghastly with wounds.”

A San Francisco paper, the Daily Evening Bulletin wrote:

“…the assassins…stealthily approached the shore and landed… They … penetrate each lodge; one holds the light to show where to strike, and while the faces of the poor women and children … are… turned up…, they begin their work of death with axes, hatches and knives. Amidst the wailing of mutilated infants, the cries of agony of children, the shrieks and groans of mothers in death, the savage blows are given, cutting through bone, and brain. The cries for mercy are met by joke and libidinous remark, while the bloody ax descends with unpitying stroke, again and again, doing its work of death, the hatchet and knife finishing what the ax left undone. A few escaped—a child under the body of its dead mother, a young woman wounded, and another who hid in the bushes.

In an hour they had accomplished their work and were gone, laden with the spoil of Indian blankets, leaving their victims strewed around, weltering in their gore—some dead, some dying, some writhing in pain and anguish, exhibiting a scene such as not tongue can tell, and no eye had ever seen before on our continent, even thought savages practiced in cruelty were the perpetrators.

Reader, this is no fancied sketch, no exaggerated tale; it falls short of the stern reality. But a short time after, the writer was upon the ground with feet treading in human blood, horrified with the awful and sickening sights which met the eye wherever it turned. Here was another fatally wounded hugging the mutilated carcass of her dying infant to her bosom; there, a poor children of two years old, with its ear and scalp tore from the side of its little head. Here a father frantic with grief over the blooding corpses of his four little children and wife; there a brother and sister bitterly weeping an, and trying to soothe with cold water, the pallid face of a dying relative. Here, an aged female still living and sitting up, though covered with ghastly wounds, and dyed in her own blood; there a living infant by its dead mother, desirous of drawing some nourishment from a source that had ceased to flow.

The wounded, dead and dying were found all around and in every lodge the skulls and frames of women and children cleft with axes and hatchets, and stabbed with knives, and the brains of an infant oozing from its broken head to the ground… “

Cousins Matilda and Nancy Spear gathered up their three children at the start of this massacre and hid with them on the west side of the island. Afterwards, they found seven other children left alive. They put the entire group in a canoe, rowed them across the bay, and then walked to Matilda’s husband’s homestead in Freshwater. Nancy later described the massacre to her nephew:

“They came like weasels in the night, crawling on their bellies. We were without any men to protect us. We had never fought the white men and had thought they were our friends.”

– (The Matilda & Nancy Spear Memorial Foundation. Brochure. Photocopy in the “Indian Island Massacre” file, Humboldt County Collection, Humboldt State University Library, Arcata.) Source.

Robert Gunther, who had heard the cries that night and would later take posession of the entire island, gave a speech on these events at the Old Sequoia Yacht Club during a banquet:

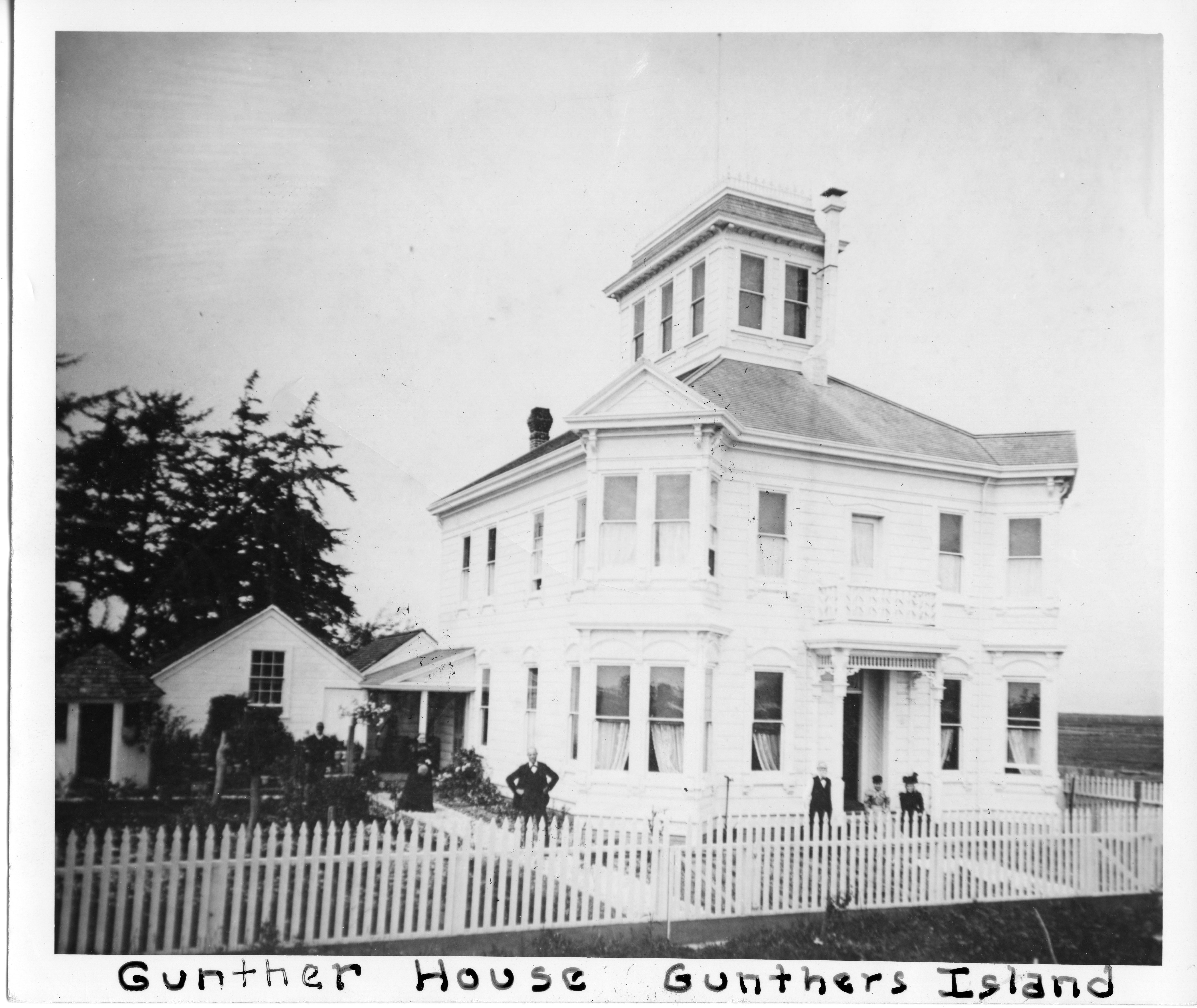

“Early in 1860, I learned that Indian Island was for sale. It was owned by a Captain Moore who took up eighty acres on Washington’s birthday, 1860, and three days later, the Indian massacre occurred. The general impression is that Indians were only killed on Indian Island, but that is a mistake. Indians were killed that night all over the Bay, and even up on Mad River. There were Indians living on Elk River, on Humboldt Point, on the South Beach, on the North Beach, on Indian Island and on Mad River, and all were killed that night who did not make their escape. It was never publicly known who did the killing, yet secretly, the parties were pointed out. Nor was their number definitely known. Some claimed there were six, while others claimed seven. It was said that about two hundred fifty Indians were killed that night.

The Indians on Indian Island, (now Gunther’s Island), were living on the upper mound towards Arcata. Every year, they had a festival which lasted a week. The festival was in full blast when I bought the island. Saturday was the last day, but as the wind blew furiously from the northwest, the Mad River Indians could not go home, but those living south did. I occupied a room then, in the Picayune mill office, which stood on the wharf right opposite where the Indians lived at the foot of K Street. Sunday morning, I was awakened by a noise, and I got up to see what it was. When I came out everything was still again. Shortly after, a scream went up from many voices, and I could plainly hear it was on Indian Island, for it was perfectly still and dark. Hearing no more, I went to bed again.

Early in the morning Captain Moore came down and asked me to lend him my boat as he wanted to go to Indian Island. He had heard the trouble before daylight and I would go with him.

When we came to the Island, we found Hatteway’s squaw, who lived on the Peninsula, sitting on the bank crying. She knew both of us and seemed to be glad to see us. But what a sight presented itself to our eyes. Corpses lying all around, and all women and children, but two. Most of them had their skulls split. One old Indian, who looked to be a hundred years old, had his skull split, and still he sat there shivering. There was no one there but three squaws, Hatteway’s and two belonging to the Island. Hatteway’s squaw told us that she was sitting where she sat when we came, and she could not sleep.

She said she saw them coming. She ran to the shanties and hollooed that white men were coming and the Indians got out as fast as they could. She stood on a low place as they came up the bank and saw them distinctly against the sky, and she thought there were six or seven. When she saw they came to kill them, she ran for the brush which was close by, and everybody else ran.

All the men got into the brush but two, but the women and children were killed. The white men did not dare to go into the brush, but left after they had killed all they could find.

The squaw told us that forty in all were killed, but that many belonged to Mad River, and that the Mad River Indians took their dead along, as they went home.

There were twenty-four dead lying on the ground, so sixteen must have belonged to Mad River. The old man I spoke of, and a little child, died later. The child was a bout two years old and was dressed. We could see no injury, but it cried when we moved it. We asked permission to take the child with us to a doctor, and the squaws were willing.

By that time some more people had come over from Eureka and we left. On the way home, we planned to bring the parties to justice. Captain Moore was justice of the peace. We soon found that we had better keep our mouths shut. We took the child to Dr. Manley. He examined it and found the spine out. He said it could not live, and we had better carry it back, and we did.

That massacre gave impetus to the Indian War in Humboldt County. The war did not start right away, but soon after, and it lasted over three years. After buying part of the Island I soon managed to get the rest. I took up land, and others took up land and I bought them out. There were no Indians living on the mound where my house stands, when I bought the place. The last family moved away to the upper mound in 1857, when Captain Moore took up the place.

After the massacre, the government gathered up all the Indians on the Bay and took them to Smith River. The lower mound was covered with brush. Both mounds were made by the Indians. They boiled and baked clams and feasted when the tide was out until the clam shells rose above tide water, then they built permanent habitations. There are places on both mounds where the clamshells were 22 feet deep, and Indian bones and relics can be found all the way down.

The number of people killed on the night of February 25, 1860, has not been precisely determined to this day. Some writers include the total number killed during the four simultaneous attacks; others include only those killed on Indian Island. The most conservative estimate is forty human beings wantonly slaughtered. The highest figure is given at more than two hundred souls murdered.”

The coordinated attacks continued in similar fashion to those carried out against Indigenous Peoples all over the world. That same morning of February 6, vigilantes carried out mass killings at nearby South Beach and Eel River communities. It is estimated that 36 to 57 Wiyots were killed at South Beach including 11 women, 14 children and 4 elders.

The determination to destroy all Wiyot communities on Humboldt Bay continued. On the morning of February 29th, 35 Wiyots were massacred near Eagle Prairie on Eeel River. A nearby village was also targeted and the following night an unknown number of people were killed.

One week after the massacre at Tuluwat, 5 separate attacks had resulted in the murders of at least 285 Indigenous Peoples.

The Humboldt Times concurred with these tactics, publishing the belief that there were:

“two-and only two- alternatives for ridding our country of Indians; either remove them to some reservation or kill them.”

Meanwhile, operations at Fort Humboldt continued, ranging eastward and continuing on campaigns of murder.

In southeastern and southwestern Humboldt County, some of the most active resistance came from Chief Lassik’s band, which succeeded in driving the settlers out of their territory. Chief Lassik and his band were captured in 1862 and held for a time on the makeshift “Indian prison” created out on the Samoa Peninsula in Humboldt Bay. A local newspaper editor toured the prison and estimated there to be 700 to 800 Indigenous Peoples therein. After transfer to the Smith River Reservation, they were able to escape and head south along the Klamath River and “stirred up discontent and revengeful feelings.” Although Chief Lassik was eventually caught and murdered in 1863, for over one year he was able to carry on a campaign of resistance against the settlers. Source.

Lassik’s niece Lucy (pictured below) recounted the story of his death (Source)

“At last I come home. Mother at Fort Seward. Before I get there, I see big fire in lots down timber and treetops. Same time awful funny smell. T (sic) think someone get lots of wood.

I go on to house. Everybody crying. Mother tell me, “All our men killed now.” She say white men there, others come from Round Valley, Humboldt County too, kill our old uncle, Chief Lassic, and all other men.

Stood up about forty Inyan in a row with rope around neck. “What’s this for?” Chief Lassic say. “To hang you dirty dogs,” white men tell it. “Hanging, that’s dogs death,” Chief Lassic say. “We done nothing to be hung for. Must die, shoot us.”

So they shoot. All our men. Then build fire with wood and brush. Inyan been cut for days. Never know it their own funeral fire they fix. Build big fire, burn all them bodies. That’s funny smell I smell before I get to house. Make hair raise on back of my neck. Make sick stomach too.

The following is from the Wiyot Tribe’s home page:

Although the white men involved in the Massacre on Tuluwat were locally known, no charges were ever filed. Remaining Wiyot temporarily took refuge at Fort Humboldt (where nearly one half died of exposure and starvation), and later were forcibly relocated to reservations at Klamath, then after a devastating flood in 1862, to Hoopa, Smith River, and Round Valley.

The Wiyot people did not disappear and attempted to return to their homeland. Often, they found their homes destroyed and lands taken. Wiyot cultural practices and language were discouraged by official policies of “acculturation.” Wiyot people learned to work and live within the white community, effectively “walking in two worlds.” Wiyot people often went to white schools, married European immigrants, and helped to build the timber, fishing and agricultural industries.

In the early 1900s, a church group purchased twenty acres in the Eel River estuary for homeless Wiyot people. The Federal Government later transferred this land into trust status in 1908. This land became known as the Table Bluff Rancheria of Wiyot Indians, now referred to as the “Old Reservation.”

In 1961, the California Rancheria Act terminated the legal status of the Tribe, and the Wiyot effectively became non-Indians Indians. In 1975, the Tribe filed suit against the Federal Government for unlawful termination, and in 1981 federal recognition and trust status was reinstated in Table Bluff Indians versus Lujan (United States). In 1991, during another lawsuit regarding drinking water contamination and other sanitation issues on the Old Reservation, the court-mandated new land be purchased and the Tribe moved to the present 88 acre Table Bluff Reservation. The original twenty acres were put into fee simple ownership under individual families but still are under the Tribe’s jurisdiction as long as held in Indian hands. The two reservations are within one mile of each other.

RENEWAL AND RESTORATION

In 2004 the Eureka City Council unanimously approved a resolution to return the northeastern tip of the island to the Wiyot Tribe, and a decade later the Tribe resumed its traditional world renewal ceremony.

In 2016 the Eureka city council unanimously agreed to return the rest of the island to the Tribe. Unfortunately, Rob Arkley, described in an article by the Lost Coast Outpost as “Eureka’s notorious real estate tycoon/political powerbroker/bankruptcy expert” has spoken out in opposition to this move. He is quoted in the Lost Coast Outpost as saying

“We’re giving it away!” he protested. “To the natives! We already gave them one thing. Now we’re giving them another? I don’t know what these— the women on the city council are thinking.”

-Rob Arkley Source.

Listen to Rob Arkley’s keen(ing) analysis of this issue:

THE HONOR TAX

WHAT IS THE HONOR TAX?

From the website : The Honor Tax is a way of recognizing and respecting the sovereignty of Native Nations, and implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

This is a “tax” out of respect for Native Sovereignty – rather than a gift or donation. We all live on traditional Native homelands. If you do not live in Wiyot territory you can initiate an Honor Tax in your community!

The Honor Tax was not in any way initiated by the Wiyot Nation, although they have formally agreed via their Tribal Council to accept the Honor Tax. The Honor Tax was initiated by individuals, organizations and businesses who want to actively recognize the sovereignty of the Wiyot tribe and their right to their traditional land.

The Honor Tax is a voluntary annual tax paid directly to the Wiyot Nation by people who are on their traditional territories. The amount is decided by the individual. Source.

To contribute to the honor tax, follow this link

July 1, 2004 North Coast Journal: The Return of Indian Island

October 27, 2016 North Coast Journal: An American Genocide.

August 30, 2017, North Coast Journal: Arkley Emails Foreshadow Litigation over Tuluwat Island.

February 15, 2018, North Coast Journal, Wiyot Tribe Votes to Remove McKinley Statue.

February 22, 2018, North Coast Journal: Making Amends on the Plaza.

August 2, 2018, North Coast Journal: The Flower Dancers – Reviving Hupa coming-of-age ceremonies.